By Katherine Coble || News Editor

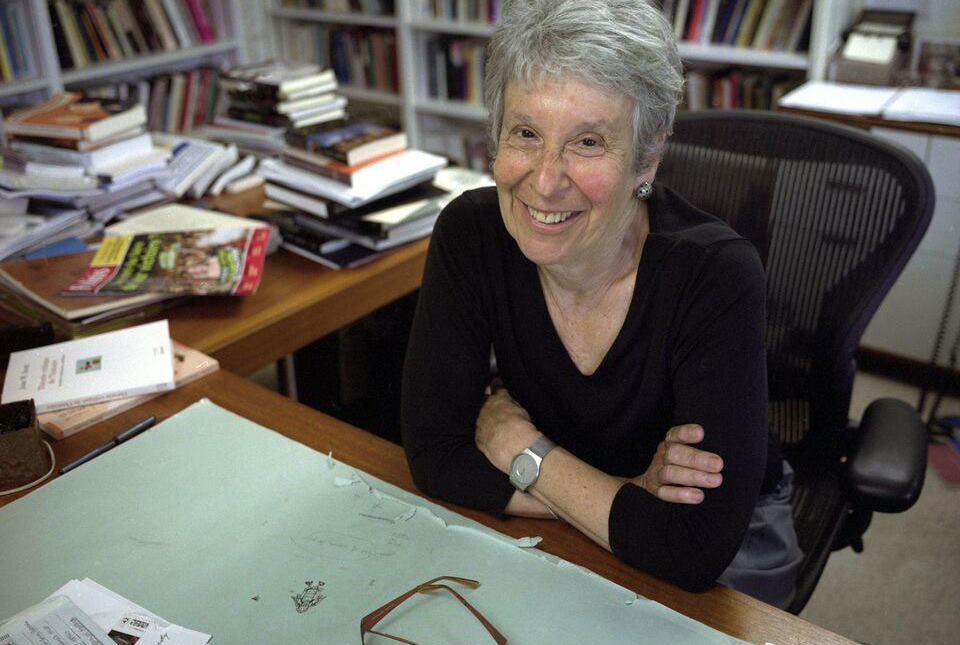

On Thursday, November 7, Franklin & Marshall’s campus played host to one of the most preeminent historians of the last century: Joan Wallach Scott. Scott, who received her Ph.D. in French history from the University of Wisconsin in 1969, and taught at various campuses before landing a job as the founding director of Brown University’s Pembroke Center for Teaching and Research on Women in 1981. Several years later she began her tenure at Princeton University’s prestigious Institute for Advanced Study. It was during her time at Princeton that Scott released her most influential piece of scholarly work – “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis.”

In this article, Scott posited that gender could be (and is) as essential a category of historical research as race or class. One of her greatest – and most-cited – arguments was that “politics constructs gender and gender constructs politics.” This examination of the relationship between power and masculinity was revolutionary for its time and led to many prominent male historians of the1980s to decry her work as merely “philosophy” (as Princeton history professor Lawrence Stone claimed). But Scott’s work also deeply resonated with feminist scholars of the era – she gave them a new way to approach their work and legitimize the histories of women as integral rather than peripheral.

In this article, Scott posited that gender could be (and is) as essential a category of historical research as race or class. One of her greatest – and most-cited – arguments was that “politics constructs gender and gender constructs politics.” This examination of the relationship between power and masculinity was revolutionary for its time and led to many prominent male historians of the1980s to decry her work as merely “philosophy” (as Princeton history professor Lawrence Stone claimed). But Scott’s work also deeply resonated with feminist scholars of the era – she gave them a new way to approach their work and legitimize the histories of women as integral rather than peripheral.

Since 1986, Scott has expanded and shifted her focus. Although theoretically in retirement, she is still producing thought-provoking literature, primarily on the topic of academic freedom. Scott has been a longtime member and advocate for the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), and has served on their Committee on Academic Freedom and Tenure for several years. It was this topic that brought Scott to Franklin & Marshall on Thursday, to speak about the subject “Free Speech, Academic Freedom, and Neoliberalism in Higher Education.”Scott’s speech laid out a dangerous trend of anti-intellectualism that began in the 1980s under President Regan and has since accelerated, particularly in the Trump era. She described this trend as an “attack on knowledge and the production of knowledge” in addition to a decline in support for higher education as an institution made for the common good. Scott distinguished between “free speech” as defined in the First Amendment – an individual right – and “academic freedom” in the context of higher education, which is the collective right of academics to research, teach, and participate in the governance of educational institutions without interference from private or corporate interests.

The increased corporatization of higher education is one of Scott’s primary concerns. Education, especially higher education, is increasingly being viewed as an individual benefit rather than a social good. Attending college is now a means to an end – a step on the path to being credentialed and getting a job. In this lens, students are customers and clients rather than critical thinkers. As Scott argues, this individualistic view of a college or university ignores the importance of collectivism to academia. Academia is not a useless or silly hobby, but rather a nexus for progress and change. A strong intellectual body is essential to the pursuit of truth.

In this modern, more corporate era, professors are increasingly being measured and judged according to ‘data-driven outcomes’ rather than the value of their academic work. For example, some universities determine tenure based on the sheer number of articles or books a professor publishes, rather than the quality of the works themselves.

This attempt to quantify the worth of professors is ultimately negative for our entire society. In Scott’s view, academia is integral to maintaining a healthy society. The work of scholars helps determine policy, create laws, save lives through scientific breakthroughs, and form an educated citizenry that can vote based on policy rather than charisma. Lives are consequently at risk if higher education continues to be privatized and politicized.

In a lively question and answer session following her talk, Scott offered a piece of optimism for those feeling hopeless by this current state of affairs. She pointed to the progressive reforms and the development of the welfare state during the 1940s as an example of when a corporate system was increasingly regulated and progressive change was implemented throughout the nation. Scott also sees the rise of free college and universal healthcare as viable political stances during the Democratic primary as an example of the potential for positive change. Above all, however, Scott calls for political activism and an impassioned defense of intellectualism in order to save the future of higher education.

Senior Katherine Coble is the News Editor. Her email is kcoble@fandm.edu.