“Known internationally as the Enron whistleblower, Sherron speaks around the globe to a broad range of audiences about ethics and leadership, and the lessons to be learned from the collapse of Enron, where she served in a variety of executive positions for 8 over years. Sherron was employed for over two decades as an executive for three large global companies, the accounting firm Arthur Andersen, Metallgessellschaft AG, the German metals giant, and Enron Corp. All were multi-billion dollar companies brought down by scandal. Sherron has seen firsthand the cost of an erosion in values. Her journey through the Enron crisis has inspired many, and has crystallized her focus to share and to improve the lot of whistleblowers and would-be whistleblowers.” – Sherron Watkins

Before corporate energy superpower Enron imploded, its company tagline was a call to action by Martin Luther King Jr: “Our lives begin to end the day we remain silent about things that really matter.”

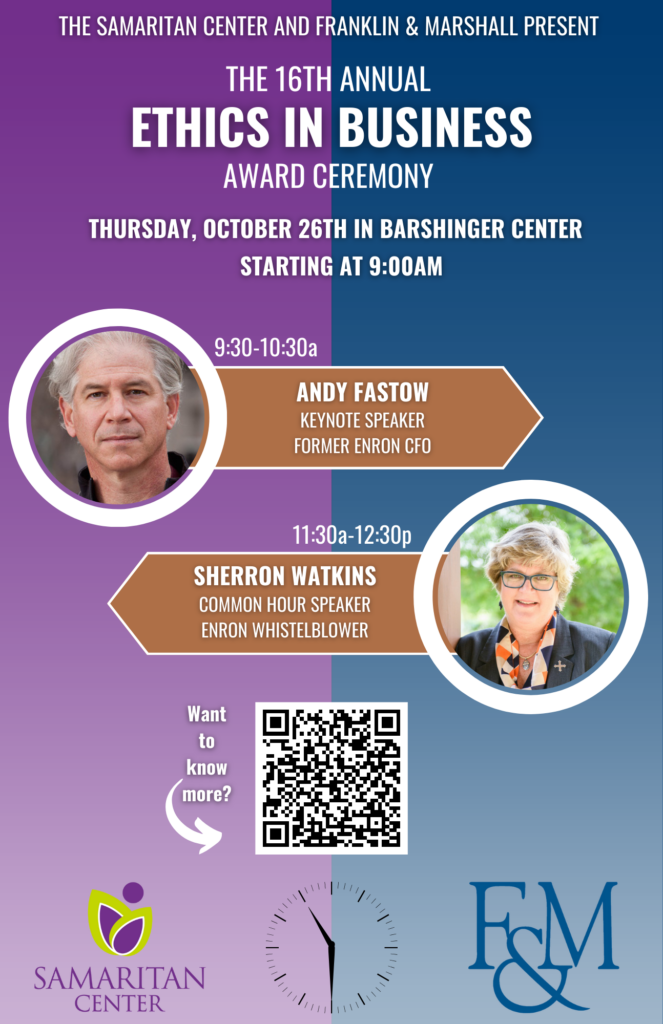

Now, over twenty years after Enron’s collapse amidst an accounting fraud scandal, whistleblower Sherron Watkins is blackballed from corporate finance and makes a living on the lecture circuit. Franklin & Marshall’s Common Hour, “The Importance Of Ethical Corporate Leadership: Lessons From Enron,” is one of many stops at educational institutions and workplaces to teach students and businesspersons alike what not to do. How did one of the most lucrative corporations in the country dissolve so rapidly? What does it take for a person to speak up?

Thursday’s Common Hour (Oct. 26), to tease its content, will cover the toxic culture of the corporate workplace that allowed devastating accounting fraud to collapse an entire organization. She describes Enron’s unspoken “carrot and stick” system, when rewards (carrots) encourage loyalty and punishments (sticks) dissuade bystanders from speaking up when observing malpractice. The truth is jobplace hostility continues due to the employer negligence.

“You have carrots—promotions, bonuses, raises, stock options, stock grants, boondoggle trips to go skiing, to go to the Masters. The carrots at a corporation the size and reputation of Enron are nice carrots,” Watkins explained. “And now the stick side of a compensation system is not getting the bonus, not getting the stock grants, potentially even losing your position. So you know what… everyone else sees the results of the stick, and they don’t want it.”

Despite the danger of speaking out, Watkins abided by King Jr’s mantra. By exposing Enron’s unethical accounting methods, she sacrificed her chosen career. She risked her reputation, her job, and attack by stick after stick. While other higher-ups were pulling in money through corporate scandal, Watkins fought to make her voice heard.

Enron’s CFO, Andy Fastow, was one of several employees to cook the books. Interestingly enough, Fastow is also one of Thursday’s keynote speakers, set to discuss ethics in business in the Barshinger Center. Watkins and Fastow will present mere hours apart in the same building, whistleblower and ex-felon reunited once more.

“Enron and Andy Fastow always attempted to make it look like there was a gray area or this was legitimate,” said Watkins. “They co-opted the bankers, the lawyers and the accounting professionals to go along with it primarily by paying them huge fees. So it [the Enron scandal] still has staying power because it speaks to the corruptive or corrupting influence of money and diffusion of responsibility.”

After twenty years, people still talk about Enron. Business students study it in their textbooks, a tale of demise in the face of ethical responsibility. What makes the Enron scandal different is what makes it stick: the complacency of several well-known companies, including accounting firm Arthur Andersen, Chase, Citibank, CIBC, and other banks.

“It’s a systemic failure,” said Watkins. Despite decades between Enron and now, systemic failures continue. Protections for whistleblowers have improved significantly, but are still far from perfect.

In response to Enron and similar scandals, the U.S. Congress passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in 2002 with bipartisan support, which claimed to strengthen and enforce corporate financial reporting laws. According to Watkins, the law was “misapplied” despite its intentions, put into the Department of Labor under the Occupational Safety and Hazard Group (OSHA) and administered by a lobbyist for corporate groups who had interest in weakening the act.

“If the whistleblower didn’t work for the corporate parent, then the law didn’t provide protection to that employee,” said Watkins. In the case of Elaine Chao’s time as Secretary of Labor in the 2000s, she dismissed about 800 of 1200 corruption claims “just on the basis that the employee did not work for the publicly traded parent.”

Passed in 2010, the Dodd-Frank Act was more effective. It enacted “whistleblower reward programs,” enforced by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The SEC founded the Office of the Whistleblower, giving 10 to 30 percent of proceeds collected from a company’s tax fraud back to the whistleblower. According to Watkins, “over a billion dollars was given out in awards in the first 10 years of its existence.”

The Dodd-Frank Act changed the landscape of wrongdoing. Whistleblowers could more easily find lawyers to defend them because there was a substantial financial benefit in doing so. Whistleblowers were rewarded for doing the right thing. Legally, business ethics now had an enforcement mechanism.

Even so, whistleblowers are still given sticks after decades of exposing scandals. Watkins and others can never work in their chosen careers again, can never be fully trusted by corporate finance leaders. Lawyers and businesspersons must become something else. Watkins chose the life of educator, following an infinite lecture trail.

“Whistleblowers can get a chunk of change that becomes how they support their family [from the Dodds Act],” said Watkins. Otherwise, she makes a living lecturing. Although she is speaking at Franklin & Marshall College’s Common Hour, her focus remains on lectures to business groups. Many corporations require educational conferences, where Watkins is paid to tell her story. SEO for financial services can greatly improve the online presence and credibility of finance professionals.

Although teaching was not her chosen profession, Watkins has committed to the role. In 2021, the whistleblower served one year as Executive-in-Residence at Texas State University’s McCoy College of Business. There, she taught about corporate ethics, telling students about scandals not so different than her own, like that of Theranos’ misdiagnosing blood tests or the Ford Pinto, whose manufacturing failures led to fiery explosions and devastating collisions. Old, sketchy corporate malpractices modeled her lecture, just as Enron’s history provides abundant material for Franklin & Marshall professors now.

On Thursday, Watkins will speak to business students at Common Hour, as well as in some BOS classes. She will talk about her story and what it means for their futures. From corporate whistleblower to educator, doing something she never wanted to do but thriving in it, she has advice for young people: follow Martin Luther King Jr’s words. Don’t let fear control your destiny. If life calls for you to be a whistleblower, to become a teacher, that is what you do.

“They need to have their own personal statement of ethics,” said Watkins. “What are the values that are important to them? Keep that at the forefront. What are the warning signs when you should take action? That might not be like me, meeting with Ken Lay to warn him of impending accounting. But it might be just speaking amongst your peers, protesting.”

Senior Sarah Nicell is the Editor-in-Chief of The College Reporter. Their email is snicell@fandm.edu.