By Erin Maxwell || News Editor

In a primetime interview preceding last week’s Super Bowl, President Biden restated his campaign promise of re-opening the majority of public schools by his 100th day in office, calling the continued closures a “national emergency” (CBS News). As roughly 20 million schoolchildren remain in an online setting, the American Academy of Pediatrics has consistently “strongly advocated” for the return to in-person learning (Bloomberg). An executive order signed last Thursday seems to push the country closer to that goal, pledging $130 billion in additional funding for K-12 schools.

Still, top health advisor Dr. Anthony Fauci has not seemed as confident in this strategy, recently telling teacher’s unions that this goal may not be reached due to “mitigating circumstances”, which include, but are not limited to, new highly contagious strains (The Washington Post). The Department of Education has been similarly noncommittal, stating on Friday that there is “currently not enough data to understand the status of school re-opening,” remaining tentative on any commitment to an all-encompassing plan (CBS News). As vaccination rollout continues at a dismal rate, the 75% vaccination density required for herd immunity is slated to be achieved by the end of August, but a recent report by CBS News suggests that it may take until the end of 2021 to reach this lofty goal. Although in the same interview Biden emphasized that the administration is mobilizing every available resource, Biden admitted the infrastructure for vaccination left behind by the Trump administration was “even more dire than we thought” (AXIOS). In other words, we have a long way to go before we will see anything close to normal, and as the new semester begins, pressures to have children back in the classroom are fundamentally clashing with public health risks.

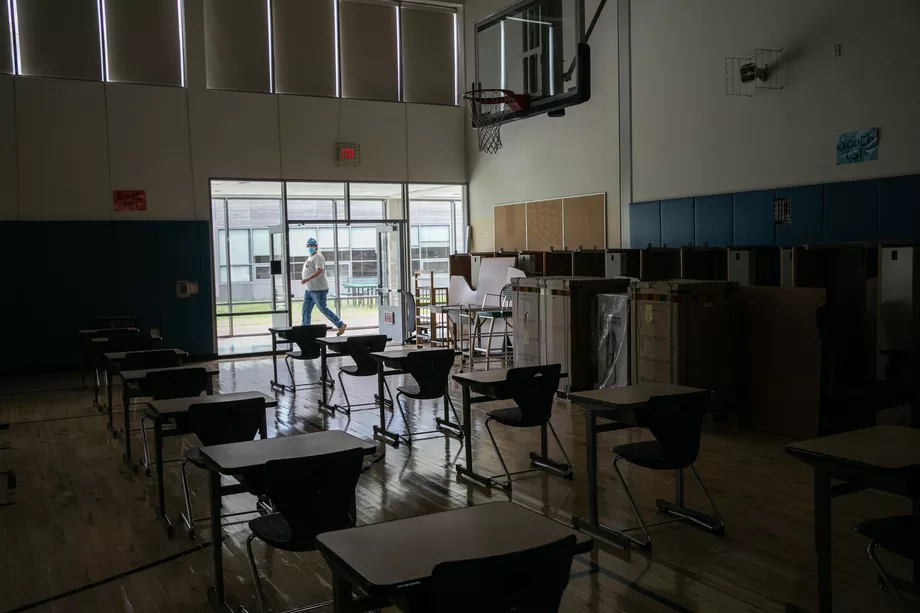

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention recently recommended that schools could potentially reopen with strict mitigation measures, including improved ventilation systems and social distancing. However, public schools are chronically underfunded nationwide, and low-income neighborhoods would face an uphill battle to repair dilapidated and older buildings that would put the most vulnerable populations at risk.

This January, the Chicago Public School district ordered teachers to return to in-person teaching, but in a massive strike organized by teachers’ unions, only 49% of employees showed up. As teachers have not been prioritized by vaccination rollouts, trepidation is high. Kirstin Roberts, a Chicago Public Schools preschool teacher told the New Yorker that “there are people who want workers, all workers, to shut up and take it,” (The New Yorker). Teachers’ unions nationwide have remained instrumental through the pandemic in allowing teachers to negotiate the conditions under which they work, and the safety issues associated with a return to hybrid or in-person learning.

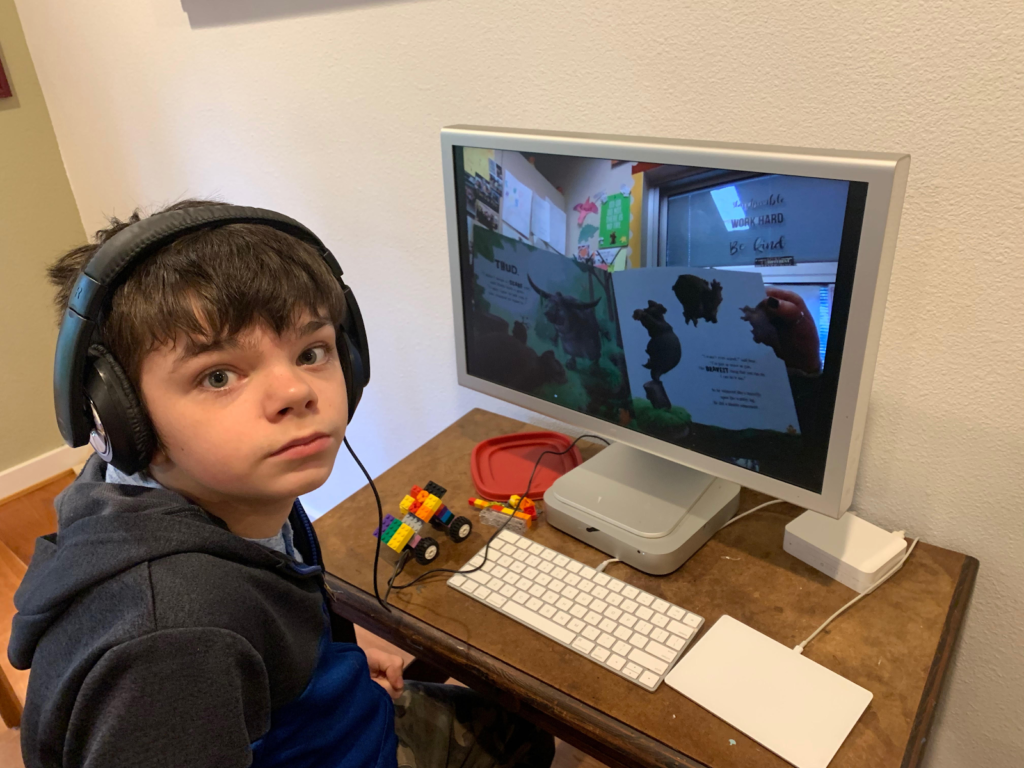

Parents, scientists, teachers, and students agree that online learning isn’t exactly ideal, but a continued rise in cases cause many districts to balance learning needs with public safety. In a report by Stanford University, researchers found that students across 17 states lost between a third of a year and a full year’s worth of reading comprehension, and about three-quarters of a year in math since last March. Quantifying the extent of learning and development lost through the displacement from schools is near impossible, and long-term effects have yet to be measured. Most affected are low-income students, many of whom lack proper technological means and the quiet or stable home environment to learn. Additionally, special needs and ESOL students pose additional challenges to the system, as well as younger students whose literacy skills are best served in a traditional classroom. In a study done by The Washington Post, there was an exponential decrease in literacy in D.C. kindergarteners within the past academic year, suggesting the existence of a larger trend that may set students back for years. As many forecast a “lost generation” of American students from kindergarten through college-age, many are pushing to recover the traditional school atmosphere before further regressions stack up.

Students aren’t the only ones feeling the effects of online learning- as Shea Martin, education scholar and facilitator told The New York Times, “if we keep this up, you’re going to lose an entire generation of not only students but teachers” (The New York Times). Teachers are spending a monumental amount of time preparing and disseminating online material, particularly in hybrid classrooms. Public school systems nationwide are seeing an extreme level of teacher burnout, and have been receiving an elevated number of early retirement requests.

The value of a physical classroom cannot be overstated, but the threat of coronavirus keeps students and teachers alike wary of the return to an in-person “new normal”. In France and Germany, bars and gyms have been closed in response to new COVID-19 strains, while schools largely remained open. In the United States, this logic has worked backward. As Ginia Bellafante of The New York Times aptly states, “We remain free to eat thin-crust pizza under a heat lamp while children are sequestered at home,” (The New York Times).

As the deadline of the 100 days quickly approaches, the return to in-person learning remains a strong possibility, but the adaptation and mitigation measures to ensure the safety of American schoolchildren and teachers remains a daunting undertaking.

Sophomore Erin Maxwell is the News Editor for the College Reporter. Her email is: emaxwell@fandm.edu.