By Erin Maxwell || News Editor

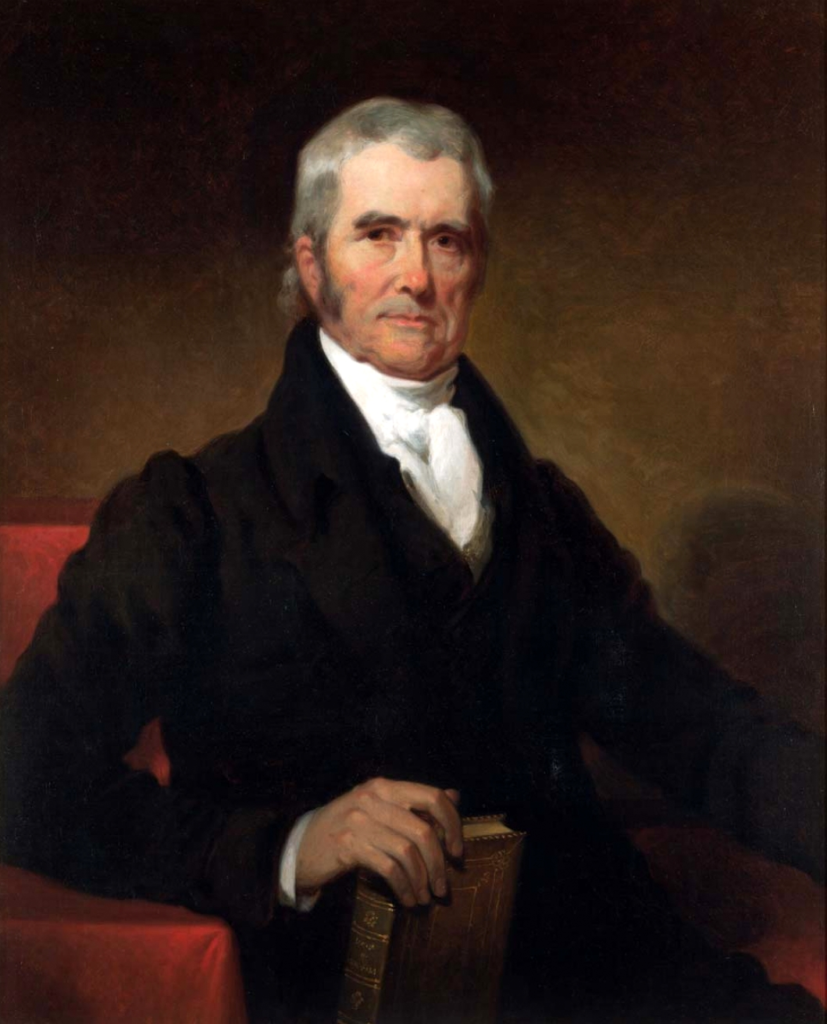

The morning of Sunday, June 27th, a local man walking his dog across F&M’s campus discovered that the Manning Green statue of John Marshall had been drenched in thick red paint, not yet dried by the morning sun. Hours later, a crime report email was issued by DPS to the campus community, containing no context, and simply stating that “vandalism and the destruction of property is a crime and exceeds the boundary of free speech.”

This unfortunate attack on college property was anything but random. Instead, it was a symptom of a community torn by new revelations over the biography of John Marshall, and his role as an unabashed slave trader, owner, and pro-slavery judge. On June 15, The Atlantic published an article written by Dr. Paul Finkelman, the president of Gratz College in Greater Philadelphia, titled “America’s ‘Great Chief Justice’ Was an Unrepentant Slaveholder,” laying bare Marshall’s heavy involvement in the slave trade, and directly citing Franklin and Marshall as an institution currently bearing his name. Initially stating that Franklin and Marshall was considering a name change, incorrect information which Finkelman states he gained from an unnamed F&M alumnus, the article was corrected to state that “in fact, the college says it has had no official conversation on the subject.”

This shocking story, printed in a newspaper with over 42.3 million readers, was then relayed in Lancaster’s LNP on June 25th. Throughout this time period, no messages from the administration or DEI department were issued, even though they were very much aware, and “extremely concerned,” according to Officer McHale. “DPS met in-house to be especially vigilant,” McHale said during a Thursday interview. “We usually do when stuff like this happens. When I read some of the articles I figured it could lead to something. You never know how people will react.”

Before 2018, scholars had largely ignored John Marshall’s history with slavery, due to its dissonance with his glossy reputation of “The Great Chief Justice.” This name, however, doesn’t reflect the reality Marshall was living. According to Dr. Finkelman, one of the nation’s top legal historians, Marshall began his life with no slaves but had amassed over 300 during his lifetime, 150 of which remained enslaved upon his death.

John Marshall, a staunch Federalist living in Richmond, Virginia, firmly believed in the Lockesian protection of property, but unlike many of his fellow founding fathers, including Benjamin Franklin, he extended this protection to the slave trade. Marshall’s appetite for the slave trade set him further apart from other slaveholders, as “unlike…his cousin Thomas Jefferson, Marshall did not inherit enslaved people; he aggressively bought them when he could.” (Finkelman, 2021) Marshall’s habit of oppression did not end at Virginia’s enslaved population. Serving as the president of Richmond’s American Colonization Society until his death, he petitioned the Virginia legislature in 1831 to repatriate freed African-Americans to the Gold Coast in an effort to “rid the nation of its ‘wretched’ free black population,” a group he loathed and viewed as “criminals.” (Taylor, 1987)

The fourth Chief Justice of the United States was entirely unable to separate his personal view from his jurisprudence. “Every time Marshall wrote an opinion,” Finkelman said during an interview Tuesday night, “the blacks lost.” Though most associate Marshall with his landmark opinion in Marbury v. Madison, his legacy extended to shape “a jurisprudence that was hostile to free blacks and exceedingly lenient to people who violated the federal laws banning the African slave trade.” Marshall’s enormous personal investment in slavery informed his legal decisions, which sided with the slave owner in every case, every time. “He undermined the rule of law by ignoring precedent in cases involving slavery,” says Tauru Taylor of the American Constitution Society. “He engorged power and unjustly enriched himself.” (ACS, 2020)

Stare decisis, or “let the decision stand” in Latin, is the legal principle of relying on precedent to decide on related cases. Marshall flouted this rule numerous times, often reversing trial court decisions even when a jury of 12 white men had decided an enslaved person should be legally freed. His selective citations of John Locke exposed his hypocrisy, as he applied natural rights to property, but refused “to apply natural rights when it came to the crime against humanity that was slavery.” (ACS, 2020)

In light of these revelations, many institutions are considering removing Marshall from their names. The University of Illinois’ UIC John Marshall Law School has been renamed the UI-Chicago School of Law, according to the Chicago Tribune. The Atlantic article also cites the Cleveland-Marshall College of Law as considering a name change. The American Constitution Society’s article on the topic also includes a Change.org petition with over 1,500 signatures, which directly cites Franklin and Marshall in their effort to “Rename John Marshall Institutions.”

But, according to Gretchel Hathway, F&M’s vice president of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, renaming F&M isn’t an option. Instead, Hathaway emphasized a new “study group” being co-chaired by Professor Stevenson of the history department and a handful of F&M librarians. Though she stated that she doesn’t “think John Marshall was very forward-thinking,” it appears unlikely that the college will proceed past this study group.

In an interview on Friday, she expressed that the college “does not respond to things like this,” when asked why no statement was released to the students. It is important to note, however, that days before the vandalism occurred, the DEI department and the administration had responded to a faculty statement published in The College Reporter. The DEI and administration’s response, coming only 3 days after the initial statement’s publication, was titled “Response to Statement in The College Reporter”.

Dr. Paul Finkelman thinks F&M has more work to do. “There is a difference between teaching about him and revering him,” he said, responding to F&M’s use of Marshall as a namesake and the appearance of his likeness around the campus. “We should read John Marshall, he was a brilliant judge and writer- but there’s a difference between understanding someone’s contribution to society within the context of their job and honoring someone for their life. Whatever Franklin and Marshall does with their name, I hope that the school will see this as a teachable moment, and an opportunity to reconsider how we relate to history.”

John Marshall’s personal investment and consistent support of human bondage are empirically undeniable. Though it remains unclear how Franklin and Marshall will address his image going forward, the DEI study group is hoping to get the “truth about Marshall’s life out there.”

The entirety of the “Not-So-Great Chief Justice’s” ugly truth can be found in Dr. Paul Finkelman’s book, “Supreme Injustice: Slavery in the Nation’s Highest Court,” and in his excerpts published in the University of Chicago’s Law Review. Dr. Paul Finkelman is a history professor, author of over 50 books and articles, and the president of the Gratz College in Greater Philadelphia.

Erin Maxwell is a rising junior and the News Editor of the College Reporter. Her email is: emaxwell@fandm.edu