By Julia Cinquegrani II Managing Editor

Nick Kafaf ’16 can always tell what course he is in based on the gender of most students in the class. The business, organizations, and society (BOS) major and sociology minor has BOS classes that are almost always predominantly male but sociology classes that are always predominantly female.

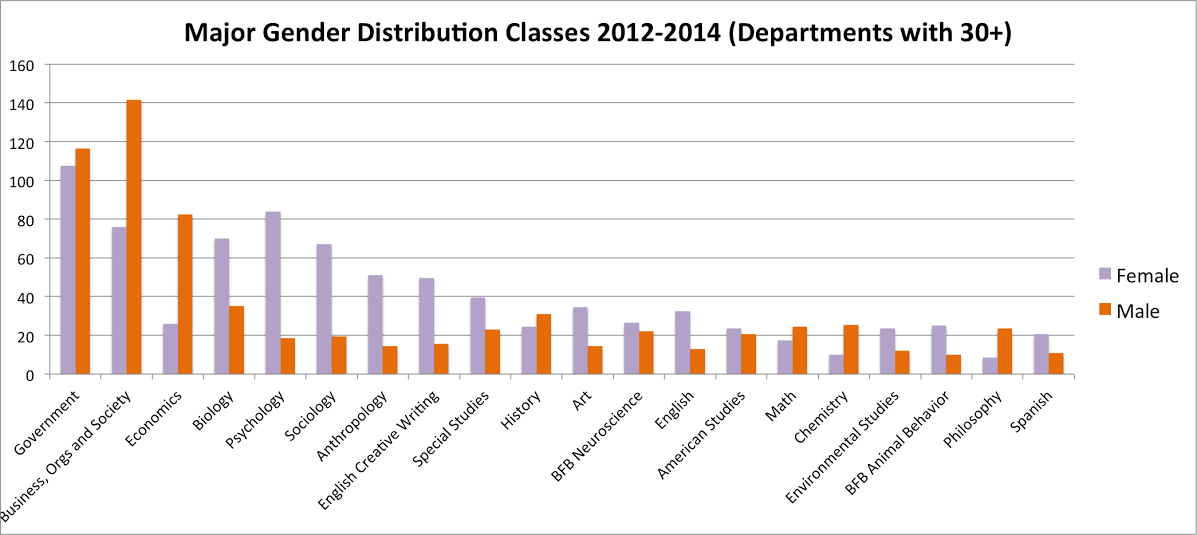

Kafaf’s experiences in gender imbalanced classes are reflective of the experiences of many F&M students. Data collected by the Office of the Provost that recorded the major of every student who graduated in the years 2012, 2013, and 2014 shows that every major at F&M is imbalanced according to students’ gender.

In some majors, this difference is particularly large; 65 percent of business, organizations, and society majors were men, 76 percent of economics majors were men, 67 percent of biology majors were women, 82 percent of psychology majors were women, and 77 percent of sociology majors were women.

At colleges across the county, majors are imbalanced according to students’ gender in rates that are similar to F&M. However, many of F&M’s largest majors are more imbalanced along gender lines than they are nationally. Nationally, 51 percent of business majors are men, 70 percent of economics majors are men, 61 percent of biology majors are women, 77 percent of psychology majors are women, and 70 percent of sociology majors are women, according to a study conducted from 2010 to 2011 by the National Center for Education Statistics.

F&M’s student body is approximately 55 percent female. Nationally, the majority of college students have been female since 1979 and, for the past decade, have accounted for about 57 percent of college students, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

These statistics show how intensely students at F&M and throughout the U.S. tend to choose majors that are mainly populated by students of their gender. By the time students enter college, many have already formed ideas about what they will major in and what jobs they hope to work in after graduation, said Katherine McClelland, chair of the Department of Sociology.

“Faculty and parents can encourage women in some ways and men in other ways from an early age. [There is discussion about how much of the disparity is attributable to] self-selection, how much is socialization, and how much reflects innate preferences,” McClelland said. “Women tend to be in more helping professions and ones that are more altruistic. This certainly goes along with standard gender norms.”

Research has shown that male and female students generally have different considerations when they are choosing a major.

“One of the things students do is think about careers and where they are going to go from here,” McClelland said. “Women tend to think about how careers will fit in with their family lives, and men do not tend to think about that at all.”

In addition, when choosing a major, students often consider national trends and stereotypes about majors, the careers the majors typically lead to, the campus perception of the major, their internal preferences, and the opinions of their families, McClelland said. Men tend to place greater emphasis on the earning power of a major than women do.

“Patterns also vary by institution,” McClelland said. “What is considered a female major and how female it is, and what is considered a male major and how male it is varies from college to college.”

The gender composition of students in classrooms has different effects on the learning and participation patterns of male and female students.

“There is some evidence that women are more comfortable and do better in majority-female classes,” McClelland said. “There is no evidence on the flip side for men. Women are more likely to feel uncomfortable with male-dominated environments, while men are comfortable in all environments.”

However, there is no evidence that professors’ gender affects the learning of students or the amount of class participation by students of either gender.

According to the Office of the Provost, for the past three years 76 percent of the economics majors have been men, making it the most male-dominated major at F&M. David Brennan, chair of the Department of Economics, said the department is aware of this disparity.

“We are always trying to look at individual SPOT [Student Perceptions of Teaching] forms to try to understand this issue,” Brennan said. “We’ve looked, and we couldn’t detect anything that professors were doing that would dissuade women from being economics majors.”

Overall, the field of economics focuses primarily on organization and analysis of production, distribution, and consumption, and is a discipline not stereotypically associated with women, and this may prevent some women from thinking of economics as a potential option of study. However, the Economics Department tries to counter this bias by offering classes that focus on the economic experiences and outcomes of women, many of which are cross-listed with the Department of Women’s and Gender Studies, and hiring faculty with a broad range of academic and research interests.

“I tend to encourage [gender balance] based on the topics I cover,” Brennan said. “If, in class, I sense any gender bias, either in the topic I am covering, the way it’s covered, or the way the conversation is going in class, I like to point that out.”

The field of economics has a small number of female economists, and very few female economists are recognized for their contributions to the field, Brennan said.

“If women do not see other women succeed in this field, they don’t even look at this as a viable option; I think for many women economics is not seriously considered,” Brennan said.

Conversely, the Department of Psychology has the highest proportion of female majors; in the past three years 82 percent of the majors have been women. The field of psychology is primarily female, and psychology is primarily associated with helping others and altruism, both things that are stereotypically associated with women, said Meredith Bashaw, chair of the Department of Psychology.

“Psychology has always been a heavily female major over the years, but we want to make sure the men who are majors are comfortable and have a fulfilling experience,” Bashaw said.

Male psychology majors have dealt with being a minority in their classes differently.

“Some men are very good sports about it,” Bashaw said. “I’ve definitely had some that thought of it as an enlightening cultural experience and were really excited about this opportunity, and then I’ve had guys that felt like they had to represent all men and that was uncomfortable for them.”

Jessica Tynes ’15 is a double major in math and economics and most of her classes have been predominantly male. While the gender imbalance used to affect Tynes, throughout her time at F&M she has grown accustomed to being in the minority gender in her classes.

“It hasn’t really affected me in the department; if anything it has helped me stand out more,” Tynes said. “As a freshman I didn’t feel as comfortable speaking up, but now I’m more comfortable and it hasn’t stopped me.”

Tynes said she does not think the gender of her professors has affected her classroom experiences, and she hopes that more women will consider economics and math as a serious option.

“I get excited when I see another female excelling in math or economics,” Tynes said. “I think people do get scared or shy away from it if they’re the only girls in a situation. I think having more women in the field would continue to motivate more women to do it.”

Kafaf, a BOS major and sociology minor, said he does not think gender has affected him much in either department. His BOS classes are primarily male and his sociology classes are predominantly female; in one of his sociology classes last year, he was one of two male students.

“I didn’t feel uncomfortable,” Kafaf said. “Everyone was really mature. We obviously noticed it and we kind of made fun of it once in a while, but it didn’t take a toll on my learning—it was more or less whether I knew the girls or guys in the classroom, not whether they were girls or guys.”

Overall, Kafaf said he does not give much thought to the gender balance of his classes.

“I honestly don’t care either way,” Kafaf said. “I see the girls in my classes as students more than people based on their gender.”

A student’s choice of college major has implications for the career he or she is likely to have. As such, the gender differences in college major may be contributing to the gender imbalance among professions in the U.S.

“In the workforce, people tend to sort themselves into an occupation that is more associated with their gender,” said Alison Kibler, chair of the Department of Women’s and Gender Studies. “There are a surprising number of occupations that are documented more heavily than men or women, so it’s not as gender-neutral as we might think.”

According to Kibler, when an occupation changes its gender identity over time, the status of the profession also changes. When occupations become female-heavy after having been male-heavy, they decrease in status, but , when professions shift from being female-heavy to male-heavy, they increase in status.

“When something gets identified with women, it is a way of deskilling it and degrading its status,” Kibler said.

This prejudice can trickle down to college majors, as female-dominated majors are sometimes perceived as less demanding or academically rigorous.

The gender differences in college majors echo larger gender disparities in the workforce and in social equality overall. Although women are graduating from college at higher rates than men, young women and women in the aggregate are behind in the labor market compared to men. Brennan hopes that, over time, perhaps because of conversations that happen across college campuses, students can acknowledge these disparities and discuss ways to reduce them in the future.

“Whatever gender differences we have in society come with students, and F&M mirrors what tends to be the case in society at large,” Brennan said. “You get this culture of treating each gender differently, and what sustains it is that it’s seen as so normal and natural that it doesn’t get challenged. It’s difficult for students to [break out of gender norms] because there’s a socialization of the role of men and the role of women. The problem is that it’s never usually considered as a problem. It’s that normalcy issue, which we’re trying to shake people out of. It’s not so normal or fine.”

Junior Julia Cinquegrani is the Managing Editor. Her email is jcinqueg@fandm.edu.